Cinematic Spotlight: South Korea

One glaring omission from everything I have covered in film thus far in The Glen Bard is the lack of international representation. Now, a lot of this is due to the fact that all of my articles have been more contemporary, as it can be really difficult logistically to catch newer films from overseas. As a result, I thought I’d start a new series of articles highlighting various countries around the world, picking out a few of my favorite films produced in the nation, and whatever other information feels necessary to include. This format will likely evolve as the series continues, so think of this as a test run of sorts. The first subject I will be covering is South Korea.

South Korea is much more well known for its tumultuous relationship with its cousin to the north than it is for its film, and that is a shame. The most well-known elements of Asian cinema hail most notably from Japan and China, however Korean film holds its own amongst the best of the best. Directors like Park Chan-wook, Kim Ki-duk, Lee Chang-dong, Bong Joon-ho, Hong Sangsoo, and a few others have entered the conservation to be considered some of the best directors alive today. These directors are often characterized by patient humanism and beautiful imagery, however, each is fully capable of a complete departure from this (see Park Chan-wook for the best example of this). Below is a small handful of Korean films to introduce readers to its cinema.

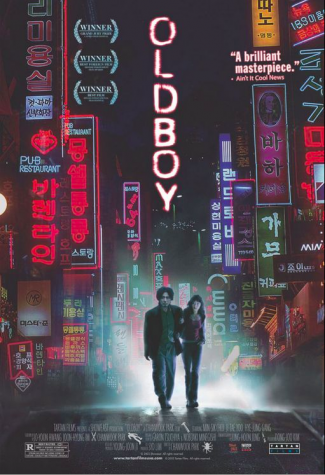

Oldboy (2003)

Perhaps the most well-known Korean film out there (Spike Lee even tried to remake it, emphasis on the word “tried”), Oldboy is a neo-noir action thriller directed by Park Chan-wook that has developed quite the expansive cult following in the years since its release. It took home the Grand Prix — the second highest honor — at the 2004 Cannes film festival, sharing this staggering distinction with legendary films like Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso, and Benigni’s Life is Beautiful among others. The film revolves around Oh Dae-su, a drunkard who immediately upon his release from authorities for his drunken behavior is kidnapped. The ensuing action surrounds his 15 years in confinement and subsequent release, where he goes on a rampage to discover the reason for his capture. Surprisingly, Oldboy is actually a reimagining of a particularly famous Greek tragedy (I’ll let you figure out which one), centered on vengeance and finding the truth at all costs. It is one of the most brilliant examples of Aristotelian dramatic structure and Freytag’s pyramid and has one of the most shocking moments of anagnorisis ever put to screen. It is incredibly action-packed and full of amazing practical set-pieces, including one especially notable long-take of an outrageous fight scene in a hallway in which Oh Dae-su takes down dozens of henchman single-handedly. Yet, despite the film’s fast-paced action, it remains highly contemplative and prefers to show rather than tell, making it equally as stimulating in this regard. Its beauty here lies in its ambiguity and selection of detail, allowing the audience to extrapolate more from the film than what it bluntly presents. Also, there’s a scene where Oh Dae-su eats a live octopus, so there’s that.

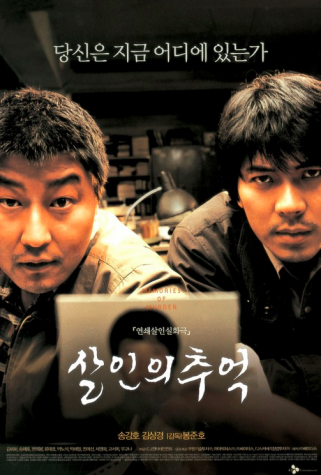

Memories of Murder (2003)

Directed by Bong Joon-ho, Memories of Murder is currently my favorite Korean film of all time. The film revolves around a series of murders that occurs in a rural South Korean province and the unprepared detectives’ attempts to solve the case and prevent further tragedy, based on a similar series of murders that occurred between 1986 and 1991. The story then primarily follows the two detectives in charge of the case, one a being brash and short-sighted dimwit and the other being an obsessive and hard-working lone wolf who looks down on his coworkers. As more and more bodies are discovered, the detectives grow more and more desperate and the town grows more and more panicked. I would say it is very reminiscent of the 2007 David Fincher masterpiece Zodiac, however, it is Fincher’s film that actually takes many parallels from this one, especially in its narrative style and patient yet building suspense. As for its visual style, Memories of Murder is a tour de force in directing, a true display of Bong Joon-ho’s prowess at the highest level. Where many similar crime-type films employ various cuts per scene in accordance with numerous shot setups at a time, Bong instead displays his mastery in composition, blocking his actors in ways that evoke the intended pathos of a scene without the overuse of annoying jumpy close-ups and frequent slow zooms to add to a scene. Each character’s position in relation to each other and their environment reveals the whole narrative of a scene. This allows him to hold on each scene, keeping the audience entranced in the narrative and the relationship between characters as the scenes progress. To go along with this, Bong frequently creates brilliant moments of subjectivity that eat away at the barrier between the audience and the film, effectively blurring the lines between the world of the film and our own. Along these lines, the film’s ending scene is one of the greatest in the history of cinema, and one of the most unique as well.

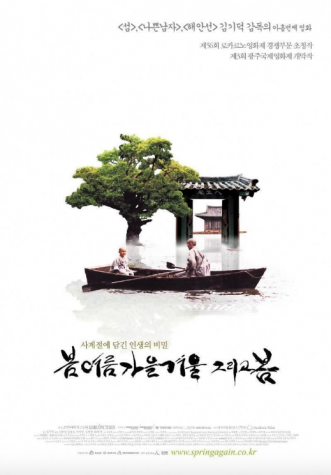

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring (2003)

Directed by Kim Ki-duk, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring is a meandering and contemplative piece about the passage of life itself, and the ups and downs it inevitably brings. The story entails a Buddhist monk and his young student living on a small floating monastery in the middle of a lake, following the young boy as he grows up through the eyes of the monk, with each period portrayed represented as a different season (hence the title). With each season comes some form of growth and regression for the child, each waking moment being watched over by the almost godly figure of the old monk. The monk is essentially the ultimate form of enlightenment, and the contrast between this state and the various transgressions of the child as he matures is where the revelations about life occur. In true Buddhist style, the film is most primarily concerned with desire, and the dangers of lust and possession. As the monk warns the student: “lust leads to desire for possession, and possession leads to murder.” It posits that this cyclical descent into the nefarious is neverending, and can only be escaped through rigorous meditation, self-discipline, and the removal of all of one’s desires. However, the most entrancing aspect of the film is not its story or themes (as is most often the case with film in general), but its tone, cinematography, and methodical pace. Director of Photography Baek Dong-hyeon captures the magical elegance of the natures that evoke an ultimate sense of peacefulness as mirrored in the monk. Director Kim Ki-duk moves slowly through the seasons, taking time for the quiet moments where all of the emotionality and philosophical applicability reveals itself. Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring feels like a leisurely ride on an old wooden rowboat through all of nature’s splendor and beauty, and it is a wonderful feeling.

Poetry (2011)

Directed by Lee Chang-dong, Poetry revolves around an elderly woman named Mi Ja (played brilliantly by Yoon Jeong-hee in what was her first role in over a decade) struggling to raise her grandson by herself while simultaneously dealing with the effects of the early stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. To cope, or to simply to learn something new, she enrolls in a local poetry class, where the target is to write one poem by the end of one month of teaching. She endeavors to capture life in verse form, but her simple dream of completing a poem is stalled by her health troubles and the heavy financial and emotional burden of her grandson’s shocking wrongdoing. Lee’s approach to the story is very matter-of-fact, or at least lacks a melodramatic sentiment that would have required a shift in the narrative’s focus and at least a much less engulfing character portrait. Lee and his DP Kim Hyun-seok keep the camera still through each scene much like the aforementioned Bong Joon-ho, and craft the entire relational narrative of a scene through blocking and scene composition. When the two do move along with a scene, the camera flows smoothly in a watchful and observational manner that feels very human and natural, which only furthers the emotionality of the film as a whole. On this front, the film deals with almost immeasurable tragedy and mostly depressing events with graceful patience and a continuous mindful eye of the beauty of the world around the film. It is highly reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s legendary Wild Strawberries (1957), with a focus on the blunt Camusian absurdism of life and the irreconcilable silence of the world, yet simultaneously able to capture the beauty in existence through the exploration of one’s passions or the acceptance of the state of the world or one’s past. Although Bergman’s work is undoubtedly more personal, self-reflexive, and much different in a narrative sense, Lee still captures this sentiment beautifully, and with a meandering grace that I treasure deeply. Along these lines, the ending scene of the film is one of the most astonishingly elegant yet entirely quaint concluding sequences I have ever seen, breaking the barriers between its world and the audience to stunning effect.

PJ Knapke is a senior at Glenbard West and a Columnist this year for the newspaper. His focus on is on film-related content, particularly reviews. He is...