Bisa Butler: Art Institute of Chicago features quilt masterpieces, first solo museum exhibition of renowned Black quilt portrait artist

Family photographs and albums composed of birthday parties, memorable moments, and random mementos are typically not thought of as fine-art. Just this morning, I found myself glancing through a set of photographs my mom took of me from 2004-2005. I was immediately struck by nostalgia, but also deep appreciation for the candidly artistic compositions that transported me back to when I was two or three.

This sense of home and familiarity is the flair and flavor that quilt and mixed-media artist, Bisa Butler, strives for in her phenomenally rendered quilt depictions of vintage and historical photographs of Black culture and community. A few weeks back, I had the honor of visiting the Art Institute of Chicago, after a temporary closure due to COVID-19, and witnessing the work of Butler in all its glory while it is currently on display.

Entitled “Bisa Butler: Portraits,” this series, which is open until September of this year, features a wide array of Butler’s works that define her portfolio. As her first solo exhibition in a museum, the proximity that the Glenbard West community and beyond has to this pivotally contemporary and narratively relevant exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago provides an opportunity that should not be missed.

While researching more on the artistic practice and beginnings of Bisa Butler’s investigation into her own Blackness and familial ties within her art, in an interview for Katonah Museum of Art, Butler discusses how she has been “an artist from the very beginning.” Growing up in a space and family life where her mother’s side was African American and New Orleans-based, and her father was from Ghana, residing in New Jersey, these blends opened her up to continual exposure to art. She was the kid that “was always coloring, drawing, scribbling” but continued to do so as she grew older. Butler shares that in her youth, “When other kids ran off to do other things, I still continued to draw,” working seamlessly with 20th century cubist artist Pablo Picasso’s quote, “Every child is an artist; the problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.”

From there, she studied art with an emphasis in painting at Howard University. The strong and modern tradition at Howard added a new dialogue and dimension into her artistic practice; the professors and deans founded the AfriCOBRA movement, a Chicago-founded coalition of artists centered around a contemporary Black narrative, with underlined focuses on pride, self-determination and the concept of Diaspora (“the voluntary and involuntary movement of Africans and their descendants to various parts of the world during the modern and pre-modern periods”).

The AfriCOBRA professors and influences at Howard helped redefine the artistic canon of the Eurocentric vision of studying the masters. Bisa Butler recalls a prompt in which the traditional white canvas was flipped to black, asking students to learn their sense of color and light from an opposite standpoint.

Ultimately, this technical and conceptual transition caused a shift for Butler. In conversation with the Art Institute of Chicago for “Bisa Butler: Portraits”, Butler began to see “quilting as an art form.” For all artists, she concedes that “it does take awhile to excavate your own soul and figure out what is driving you.”

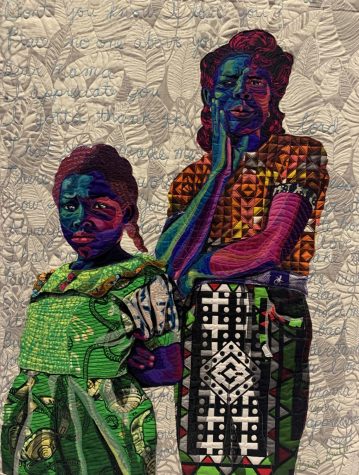

The driving force ultimately caused Butler to pick up her family photographs and picture albums again, finding inspiration with the faces of her relatives and family friends. She emphasizes that she “strove for dignity” while making these pieces and portraits and the dichotomy that emerged between the “laced up, buttoned up clothing” depicted portraits within the family photographs and the way history portrays late 19th century, early 20th century free Black and mixed-race Creole populations in such diverse media.

The wide archives of her family’s mementos are not barriers that Butler places on her references. Instead, she also studies national archives and databases in which she finds old-fashioned terminology amongst the dated fashion trends. With no names, no locations, and little context, there emits a missing puzzle piece and a lack of respect for the stories behind those pictures. “This photograph was taken, and this person obviously knew someone took their photo that day,” but beyond that, Butler showcases that nothing else is shared, explored, or questioned. The photos are then left to sit forever in an online archive. That is, until Bisa Butler had something else in mind.

Through incorporating family photographs as well as historical photos of the Black community from databases, Butler expands on the quilting skills and tradition of her mother and grandmother. She gracefully integrates culture and context, elegance and artistic craftsmanship within her life-size quilted portraits of family photographs and forgotten documentations of the history of the Black community. The exhibit of Butler’s work at the Art Institute of Chicago provides some of Bisa Butler’s greatest pieces to date.

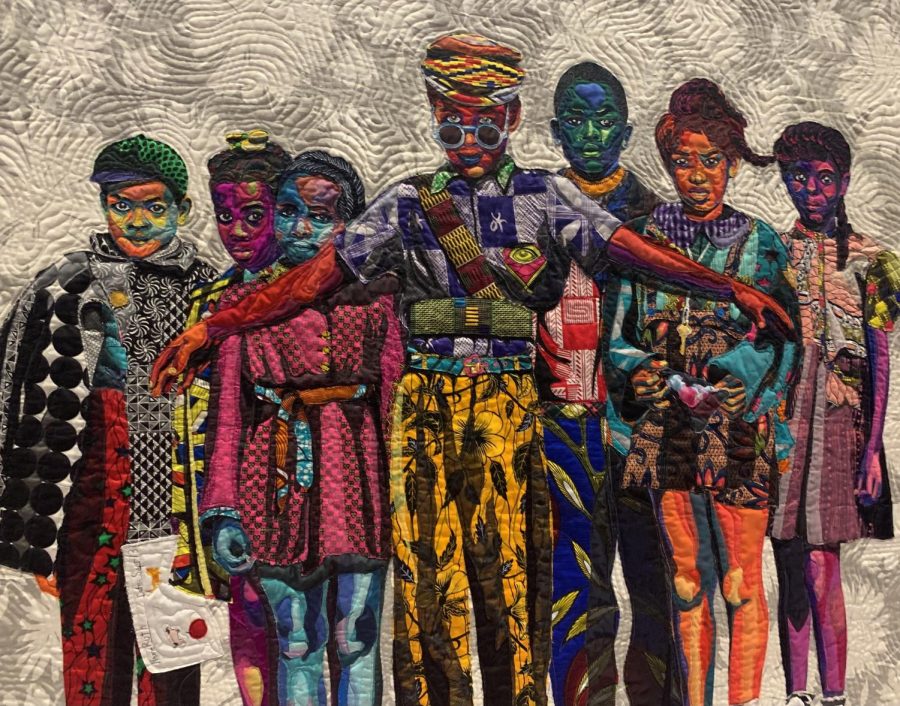

As one walks into the gallery, the first work on display is The Safety Patrol (2018). A glorious composition, the grey and white background emits a stark contrast to the direct gazes and plentiful colored layouts of the seven children greeting you. From the beginning of the collection, Butler seamlessly cuts out a photo from the history books or from the depths of her family’s nostalgia and renders old-fashioned snapshots into quilted perfection.

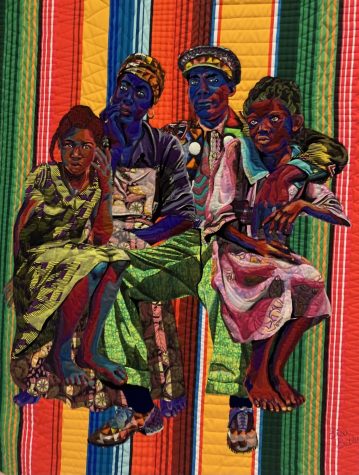

Some of my other favorite pieces from the collection besides The Safety Patrol (2018) include I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (2019), Anaya with Oranges (2018), Dear Mama (2019), and Kindred (2019).

It wouldn’t be fair of me to mention my favorite pieces without acknowledging the work of Bisa Butler and her husband, who collaborated on and compiled a Spotify playlist to be listened to throughout the gallery. While I was unable to listen to it at the time when I visited, the compilation of songs and artists matches perfectly with the nostalgic and thematic entity that is “Bisa Butler: Portraits.”

Unfortunately, there exists a certain intimacy that has been lost over COVID-19 due to the inability to see art in person, at least temporarily. Within Bisa Butler’s collection, textures and nuances of fabrics, etchings and inscribed texts are often missed when photographed, but evident when gazing into the piece in person. Whether you are a passionate artist or newbie in the art world, a Chicagoan who’s never entered the Art Institute of Chicago or a frequent patron, “Bisa Butler: Portraits” is destined to be one of the best exhibitions this year. “Bisa Butler: Portraits” runs presently until September 6, 2021 and tickets can be purchased online. As her first solo museum exhibition, this is a collection you do not want to miss.

William is currently a senior and is thrilled to be apart of the Glen Bard Editorial Board for his fourth year as the Co-Editor-In-Chief. Besides writing...