New Grading Policies Get Mixed Response From Students, Staff

As of this school year, grading policies have changed drastically for some courses. Photo courtesy of Ethan Parab.

This year, the District 87 School Board has passed a new set of grading policies, implemented across all Glenbard schools and departments. These policies include several changes, including expansion to retakes, an end to extra credit, and 80 percent summative weighting, among others. The new rules received a mixed response from West students and staff, ranging from strong support to outright opposition.

Among the practices are an emphasis on expanding reassessments. According to a release from District 87, “[t]eachers will provide consistent opportunities for students to retake or redo summative assessments.” According to Mr. Peterselli, Assistant Principal of Instruction, “that practice is meant to ensure that a student’s grade reflects their growth and most recent learning.”

“I’ve always […] been supportive of retake policies in years past. I used to have a folder downstairs where kids could come and retake as well, so it’s not really that new I think for the team that I’m a part of,” said Mr. Neiss, English 3 AP and senior composition teacher.

“I believe that the new retake policies are beneficial to the grades, motivating students to learn and grow to achieve success, even if they didn’t reach their goals the first time,” says one student.

However, according to a letter to parents, another part of the expansion of retakes was that students engaging in academic dishonesty “will receive dean’s consequences,” but will also “be required to retake/redo the assignment.” In other words, a student caught cheating will be punished by the dean, but will still get an opportunity to retake at no penalty to their grade. This part drew more mixed reactions.

“Detention is not an appropriate repercussion for, ‘Oh, I have absolutely no integrity in my course,’” responded Mr. Medic, physics teacher. He continues, “I think [it] takes away from the teacher’s ability to maintain their course and I also think it sends the wrong message to the students.”

Referring to the recent remote year, one student said, “a lot of people cheated, okay, and, if you got caught, they didn’t give a s***, […] I feel like, now, they should be a little bit stricter, a little bit, because, like, we’re in school.”

However, Mrs. Fritts, English teacher, offers a counterargument, “You’re not giving us a sample of your writing, so there’s nothing to assess. […] Of course there should be […] a school consequence for dishonesty, but the teachers still need something to assess.”

The next major change is in extra credit, or the lack thereof. District 87’s release says, in no uncertain terms, “No extra credit will be offered.” Mr. Peterselli says the concern behind this is that extra credit is “a method by which one can improve one’s grade without increasing their learning” and that, if the task is “tied to the targets and standards of a particular unit, then it probably should be included in the curriculum and not be extra.”

Ruthvik Mattupalli, a senior at West, supported the move, believing that “the old extra credit policy targeted a person’s willingness to commit.”

Another student, however, opposed the decision, acknowledging that sometimes, “it was, like RNG (random), you had to be on the winning team or whatever, but most of the time it was just you doing your work.”

One student advocated extra credit on different grounds. Considering mental health and issues outside of school, “for people who are struggling, […] it was just this little helpful thing that they’ve now taken away.”

Despite differences in opinion amongst students, teachers were generally neutral on the extra credit portion. As Mrs. Fritts said, “I think students are more upset than teachers. I think the point of extra credit was for a student to boost their grade.” She continued on to say, “in English, improving your writing is going to help you get points back” through the revision process.

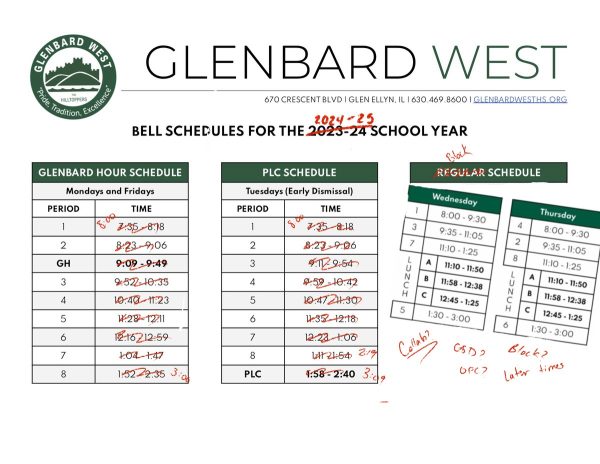

The final change to note is the new grade weighting. Now, formative assessments, generally consisting of practice work, can be weighted at a maximum of 20 percent, with summative assessments, consisting of tests, accounting for 80 percent of a grade. As explained by Mr. Peterselli, “We want to deemphasize the point value of practice so that students participate fully in that practice. If you’re always afraid that everything you do in a class is going to be high stakes and worth a lot and you’re afraid to grow and fix your mistakes or acknowledge them, you’re not going to learn as much.”

A concerned student brought up that “there’s just so many variables that could alter your test scores, like you could know the knowledge and then be tested on it on a bad day, and then get horrible grades.”

In response to the possibility of outlier scores, Mr. Peterselli noted, “that’s where reassessment […] would be a really helpful resource.”

Charlie Vanek, a junior at West, responded in support, saying, “I feel like it’s actually, like, super-duper helpful because that encourages students to study on their own what they need to, instead of, like, forcing the kids to do stuff outside of school—that’s not super helpful.”

Most teachers interviewed did not feel much change in their practices. However, Mr. Medic presented one concern, “I think trying to break anything academically into ‘This is completely summative, this is completely formative’ is not really doable. I think school education life in general is way too gray.”

Mr. Medic continued on to express an issue with the new practices in general, “You’re trying to make a blanket statement across an entire school and any policy that is applied equally to English, to math, to science, to different sciences—biology, chemistry, physics—to social studies, to gym—all of these courses are so different.”

Mr. Peterselli acknowledged room for specialization in the policy, saying, “We’re trying to have tight and loose situations because they acknowledge that each content handles things a little bit differently, learning looks different, assessments are used perhaps in a little bit of a different way and so there’s the things that are immovable […] and then there are the things that are up to each individual team,” giving some leeway for “specialization for particular teams.”

According to Mr. Peterselli, regarding grade policy, “It’s always going to be a work in progress, but we are aspiring to do it better.” Whether or not these approaches work out remains to be seen, but we can always be sure that the students’ needs will be considered, if they end up revised.

Ethan Parab is a senior at Glenbard West and a Tech Specialist of The Glen Bard. In addition to newspaper, he enjoys playing tennis, reading, and computer...