I.

On the corner of Park Boulevard and Pennsylvania Avenue, near J & R Auto Repair, lies a storm sewer grate. While this is not unusual in itself, looking through the grate and into the sewer below reveals an unusual sight. Even though it might have been days since the last storm, there will likely be water in it—and not just a small puddle, but a flowing stream of water. It could pass for a regular creek if it were not underground in a tunnel of concrete.

That is exactly what it once was.

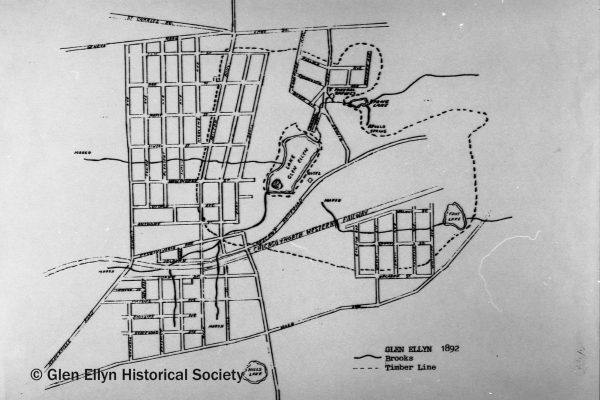

Although many might not know it now, Glen Ellyn was once crisscrossed by a series of creeks and streams, fed by marshes and springs, all flowing into the East Branch of the DuPage River. All of these streams remain, although most have been forced underground. Almost all of the springs and marshes have been filled in or drained dry by the wells which provided Glen Ellyn and the surrounding area with water.

Little remains of these creeks today except for the storm sewers they flow through, the topography of Glen Ellyn they helped to create, and the lakes in the northern part of the village—Lake Ellyn among them—which they flow into.

The story of Glen Ellyn’s creeks is a story of development and construction pitted against nature—a fight which humanity won. Like elsewhere in DuPage County, the streams which once drained marshes, prairie, and forests were forced underground, dammed, or channelized. Today, people work and live above places which once were home to fish.

What happened?

II.

When the first settlers arrived in what became downtown Glen Ellyn, the landscape they inhabited was much more rugged than it is today. The valley between Duane Street and Pennsylvania Avenue was several feet deeper, and the hill between Anthony Street and Pennsylvania was many feet higher. Deep ravines ran east of Forest Avenue and south of Cottage Avenue. To the south, Baker Hill—the hill on Roosevelt Road from Route 53 to the East Branch—was so steep that, according to Glen Ellyn: A Village Remembered (a book on the history of Glen Ellyn where much of this article’s information comes from), being able to climb it in a car earned you bragging rights. But one of the most significant differences between then and now are the streams.

There were several of them, all draining into the East Branch of the DuPage River. The main one (referred to hereafter as “Indian Creek”, a name bestowed upon it in one of the two sources which gives it one), which was rarely dry, rose in a marsh west of Western Avenue and was fed by springs and smaller creeks rising to the south as it ran through the western parts of the village.

(Interestingly, an area just north of the library has a ditch with rocks on its sides which resembles a creekbed near where Indian Creek once flowed. However, the “creekbed” now only has water when it rains, and even that has nowhere to go except into a currently clogged storm sewer drain in its center.)

Indian Creek then crossed the railroad between Prospect and Glenwood Avenues and flowed through the heart of downtown before flowing directly (or at least extremely close to) underneath the intersection of Forest and Pennsylvania Avenues. It then flowed just north of Pennsylvania, splitting Park Boulevard in two, before swinging to the north and entering a large, flat, marshy meadow. The meadow itself was later used as a place to play baseball, and was most notably the site of a 102-2 game where Glen Ellyn boys were demolished by what would become the Chicago Cubs. Today, we know it as Lake Ellyn.

From the valley, Indian Creek flowed north before swinging to the east and into a marshy area, receiving the waters of five springs to the north, and entering a small spring-fed lake. From there, it crossed more marshes before merging with the East Branch. For its entire length, Indian Creek was fed with water from springs located throughout downtown.

Two other creeks also flowed through old Glen Ellyn, the area between Hill Avenue and St. Charles Road where the village originated. One (referred to hereafter as “Linden Creek” by the author) originated in several marshes west of the village, from which it flowed directly east north of Hawthorne Boulevard into the meadow and Newton Creek. Another (referred to as “Harmon Creek” by the author) originated in a marsh between Crescent Boulevard and the railroad before crossing the latter, swinging east, and flowing into a large body of water known as Foot Lake surrounded by marshes east of Whittier Avenue. Nothing remains of Foot Lake today except old maps and documents, although Harmon Creek (despite having moved underground long ago) has had a lasting influence on Glen Ellyn. In 1890, the railroad built a bridge over the creek to allow water to drain from the area to the north; today, we know the bridge as the Taylor Avenue underpass. Harmon Creek, like the rest of Glen Ellyn’s streams, eventually ended at the East Branch, where a tiny part of it remains above ground as it flows nearly directly from a storm sewer into the river.

III.

Arguably, nobody has had as much influence on Glen Ellyn as Professor Thomas E. Hill. A man who moved to Glen Ellyn—then Prospect Park—in 1885 and soon became an influential person in the small village, eventually becoming village president. He lived south of what was then called Gardner Bridge Road (which was eventually renamed after him), and dammed a marsh and spring to the north of his estate to form a lake (now filled in). It is likely that this lake is the reason for Lakeview Terrace’s name.

Hill’s greatest contribution to the village, however, was in 1889. It was then that he came up with a plan to significantly improve Prospect Park—building an earthen dam on Indian Creek, which would turn the meadow it ran through into a large lake. His plan was put in motion. Civil War veteran Philo Stacy managed the construction, and by the next year, what became known as Lake Glen Ellyn (known today as Lake Ellyn) was formed. The lake, named after the glens in the village and Hill’s wife Ellen, was larger than it is today—it included what is now Duchon Field and had an island (called Glen Isle) around the western part of the field. The lake became a popular destination, and was used by bathers and boaters alike. It was in the same year the lake was finished that a Wheaton newspaper suggested that the entire village be renamed to “Glen Ellyn” after the lake; the name change became official the next year.

The construction of the lake did not just benefit the Glen Ellyans, however. Seth Baker, one of the two owners of the land Lake Glen Ellyn was built on along with Hill, formed the Glen Ellyn Hotel and Springs Company with Seth Riford (whom Riford Road is named after) and A. E. G. Goodridge. The company built a large hotel on the southeastern side of the lake (called Hotel Glen Ellyn), and sold water and mud from the springs to the north (which were believed to have medicinal effects—the five springs which fed into Indian Creek were found to each have different minerals in them, leading to the name “Five Mineral Springs” being bestowed upon them, and a nearby spring, Apollo Spring, was found to have extremely clear water). All in all, this had the effect of turning the newly renamed Glen Ellyn into a Victorian health resort, which it remained for some time.

Nothing, however, lasts forever. Financial problems caused the Hotel Glen Ellyn to change ownership several times, and both it and the bottling plant at Apollo Spring were destroyed by fires in the first decade of the 20th century. Over time, the Five Mineral Springs became overgrown with weeds, and today only the base of the concrete pavilion which was built around them remains. The springs themselves were destroyed when the use of wells caused the aquifer to shrink, the wells being the main way for Glen Ellynites and those living in nearby towns to get water for over a century. In 1922, the southern end of Lake Glen Ellyn was filled in and Glen Isle leveled to create Duchon Field, mostly creating Lake Ellyn as we know it. Hill himself died in 1915, but the imprint he made on the village lived on.

IV.

As the years went on, so too did development. Though we do not know exactly when, the creeks which flowed through old Glen Ellyn were slowly moved underground. Indian Creek appears to have remained above ground for a long time, although it too eventually fell victim to development. Although the exact year remains unknown, it appears that Indian Creek was mostly moved underground in 1922, when a dry goods store was constructed where it used to flow under Main Street. Today, Oak & Steel occupies the same location.

Indian Creek was not alone in being tamed by man. At about this time, the East Branch itself was channelized, and a dam built in Churchill Woods Forest Preserve around 1930 damaged the river itself, lowering the level of dissolved oxygen in the lagoon which formed. The dam was, however, removed in 2011, allowing the river to partially recover, with the lagoon, although smaller, being kept in place by man made riffles.

Still, Indian Creek remained above ground in some places. It appears to have flowed openly from Lake Ellyn to the East Branch for several years after the rest of it went underground, and even today it remains partially above ground. One can even glimpse it flowing from downtown towards the river through storm sewer grates in Ellyn Avenue and Lake Ellyn Park.

Indian Creek today exits the storm sewers in two massive pipes just east of Riford Road north of Lake Ellyn. Like the lake, it has been repurposed as a way to move stormwater away from homes and into the East Branch.

This outlet, called the Riford Channel, is the inlet to Perry’s Pond, a manmade lake formed by a dam at its eastern end. The pond itself is famous for being where a mastodon was found while the pond was being excavated in 1963 by Judge Joseph Sam Perry, the owner of the land. Today, the pond is part of Churchill Woods Forest Preserve, and the mastodon’s memory is preserved by a historical marker at Lake Ellyn Park and an exhibit at Wheaton College.

Right next to the dam which forms the pond (known by the author as “Perry’s Pond Dam”) is an unusual sight: a spring (known as “Diana Spring” by the author), similar to those which once helped to give Glen Ellyn its reputation in the 1890s. After Glen Ellyn and neighboring towns switched to Lake Michigan water from well water in the 1990s, the aquifer has begun to bounce back to its original levels. However, it is unknown if the Five Mineral Springs and Apollo Spring will ever return.

From here, Indian Creek is turned into a lake by another dam (called “Spring Dam” by the author) before entering another lake (called “Spring Lake” by the author). This lake, however, only shares a name with the old lake Indian Creek once flowed through—it is a different lake entirely, with the old Spring Lake having disappeared. The lake formed by Spring Dam occupies its location, although it does not have its old boundaries. After leaving Spring Lake, Indian Creek flows eastwards through marshlands and between cane before entering the East Branch of the DuPage River.